Pablo Sanchez Sr.

Pablo Sanchez Sr. played a vital role for both the

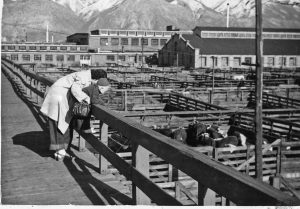

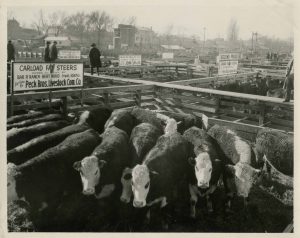

Ogden Stockyards and Swift Building

A Mexican immigrant teaches his family the value of hard work

Who fed and cared for the animals before their sale or slaughter? One man.

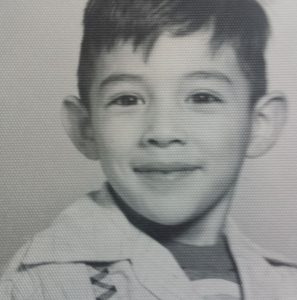

Pablo Sanchez, Sr.

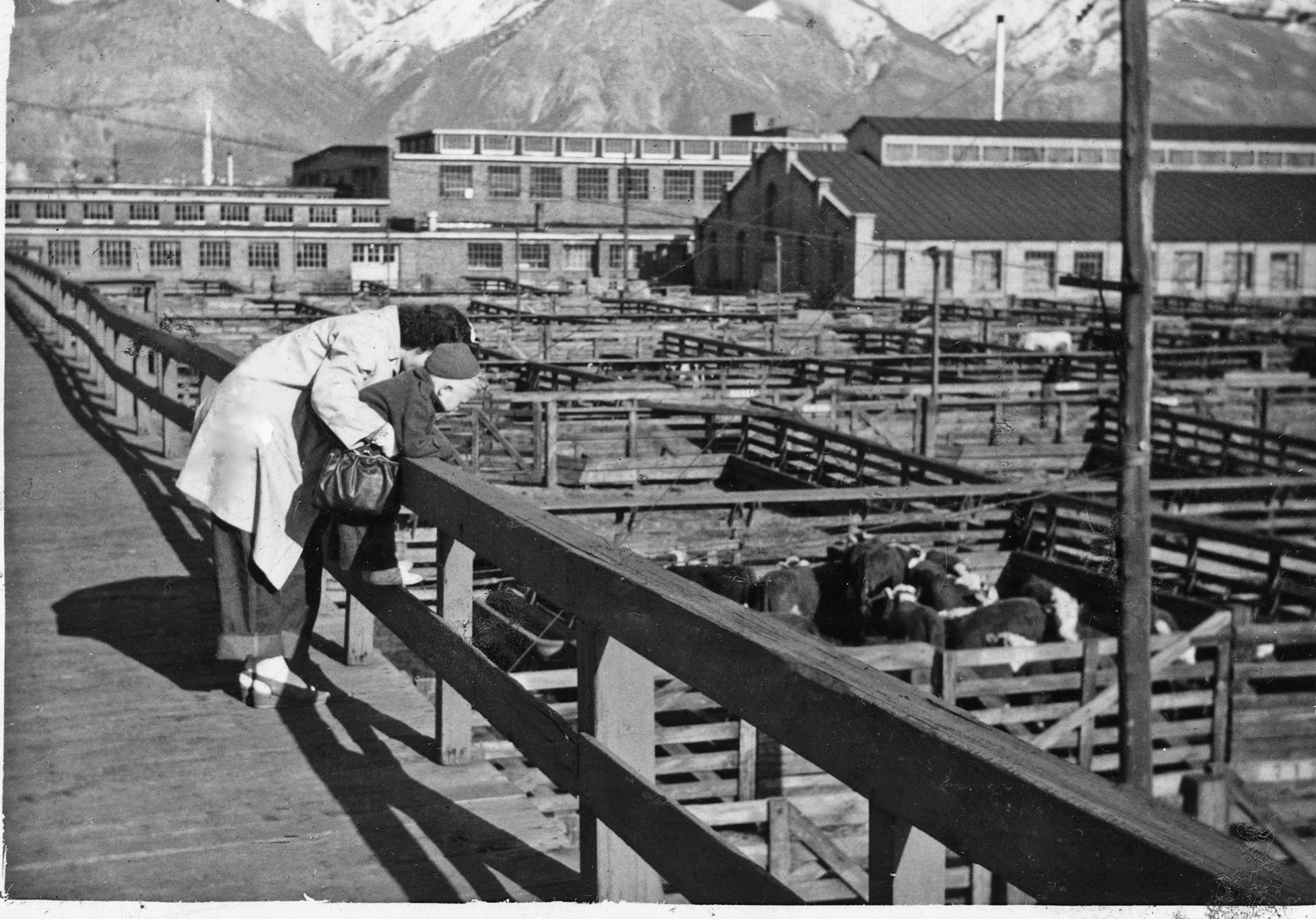

Pablo Sanchez Jr. loves to drive around the old Ogden Stockyards and area around the old Swift Building. Fond memories of his years there come racing into his mind. Not the years of his employment, but of his father’s. His father, Pablo Sanchez Sr., worked just across the river from Swift, feeding the livestock the day before their slaughter. Sanchez Jr. would go to work with his dad around one day per week during the summer months. “I think my mom just liked to get me out of the house,” Sanchez Jr. said with a laugh. But for him it was an adventure.

When Pablo Sanchez Senior immigrated to the United States as a young boy he was determined to make a difference. He did so by hard work and perseverance. His love for the outdoors and animals proved irreplaceable for the Stockyards and Swift.

A Son Shares His Father’s Stories

His dad was the sole person to feed the hundreds of livestock of sheep, pigs, goats and cattle each day. Most days he would lift 50 to 60 bales of hay for the animals and sometimes twice – once off the trucks to store in the hay house and once to deliver it to the animals. Sanchez Jr. was always amazed and how easily his father would lift the bales of hay, when as a child he couldn’t even move them. His father always laughed at him for that.

Making a Life In America

It seemed like an easy enough transition for Sanchez Sr. to work outdoors day in and day out, caring for the animals and lifting hay. He grew up in a horse ranch in Mexico and loved working outside with the livestock because he understood them. Plus, he enjoyed putting in a hard day of honest work. When his parents died in Mexico there was nothing left for him there and he moved to Ogden, Utah to be near his sister who he loved dearly. Once in the United States, he joined the Army and spent several years serving his country. He served during World War II time and although he never saw combat, he always respected the time he spent there. After returning from the Army he started working at Swift. Sanchez Jr. is unsure if he was employed by Swift, the Stockyards or the railroad or he’s not sure if the railroad contracted with Swift. That’s one of those questions he wishes he could ask now, but he passed several years ago.

Waste not, Want not

Sanchez Sr. took his job very seriously, meticulously cleaning out the animal pens each and every day. He had a systematic way of sorting the hay bales and taking the wires off each bale of hay. He saved the wires and bunched up the hay and re-used it at the end of each day. Waste was not something that he allowed in his job. He also utilized the manure by using it for fertilizer on not only his yard, but his sister’s. Sanchez Jr. said his father and his aunt’s yards were some of the most beautiful in the neighborhood because of the way Sanchez Sr. took care of the fertilizer and made the best of it. “He always considered the extra hay and fertilizer to be fringe benefits of the job,” Sanchez Jr. said with a laugh.

Sanchez Sr. said watching the process of the animal slaughter was always interesting to him. He couldn’t say how many animals were slaughtered a day, except that it was in the hundreds it seemed. The sheep would go in cycles – usually 200 at a time. While the animal pens and hay buildings were in close proximity to the Swift Building, it was still a process to get the animals to the building. The animals were on the other side of the river from the Swift building close by the train tracks that the animals were brought in on regularly. Sanchez Sr. was not in charge of releasing the animals for slaughter, there were two other men who did that job, but he would often watch and could step in and assist if needed.

He always cleared the roadway for the animals before they were released so the animals could pass safely along the road and the bridge to the kill floor of the Swift Building. Sheep were led across the river to Swift and up the ramp by goats that were dubbed “Judas goats.”

“The goats were amazing and we would often give them names,” Sanchez Jr. said. He especially came to love one goat that they named “Billie.” They would put a large bell on the goat and it would parade back and forth with the bell on in front of the pens. The animals would be mesmerized by the goat and the bell and as soon as the pens were open they would follow right behind the goat. The goat would them lead them across the bridge and over the Swift Building. Once to the building, the goat would lead them to the ramp and then the livestock would part ways with the goat. The goats would always return back to the pens. The animals had to walk up almost to the top of the building on the ramps to what was called the kill floor where within moments they would be slaughtered. Sanchez Jr. said it was amazing how they did it each and every time and how the goats knew where to take them…and when to leave.

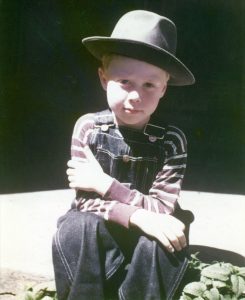

Helping Dad at Work

Sanchez Jr. got a kick out of walking between the pens and checking out what the animals were doing. “The sheep are kind of greedy,” Sanchez Jr. said. They would get so eager to get their food sometimes they would get their heads stuck in the slats of the pen trying to get their food before anyone else could. On the days Sanchez Jr. was there, it was his job to push their heads through the slats. He loved when he would hear his name called to take on the task.

Some of the bulls were extremely mean. Especially the Brama bulls. Sometimes he would walk between the bull pens and they would charge at him. “It was scary,” Sanchez Jr. said, but he knew he was safe, so he kept doing it. One day his father came in contact with an especially mean and fierce bull. As his father walked by to feed him, the bull charged at him. His father took the gate and pushed it back, forcing the bull back. His father and the bull stared each other down for a moment. His father eyes saying, “Go ahead, come at me.” At that, the bull turned around and walked away. “It was amazing to me. That elevated my dad in my mind,” Sanchez Jr. said with a big smile. He was saying to that bull, “You aren’t going to get the best of me,” Sanchez Jr. said.

Auction Action – Tempting for a Young Boy

On many of the days Sanchez Jr. got to go work with his dad he had other adventures to check out besides just the livestock set for slaughter. There was a live auction. Sanchez Jr. loved to slip into the auction and see what the cowboys were doing. “I couldn’t ever understand anything they were saying. They would say a whole bunch of stuff and then I would hear, ‘Sold!’” Sanchez said with a big chuckle. The livestock were paraded around and cowboys of all different statures would buy the animals. It was at the auction where he saw the sickest of the animals. “You never saw any sick animals on the Swift side,” Sanchez Jr. noted. But he saw plenty at the auctions, which was something he never understood. Sanchez Jr. watched the hundreds of animals on both sides of the stockyards – the Swift side and auction side and felt lucky he got to be a part of the action. He loved that he lived in the place that was the hub of so much excitement every day.

Stockman’s Cafe – Yum!

During his weekday adventures, he would try to pay a visit to Stockman’s, the yummy restaurant just across the street from the Stockyards. Workers would often toss him a quarter or dime during the course of the day and tell him to go get himself a soda. He was happy to oblige. When he would go inside, being the young kid he was, the employees made a big deal of him. They knew his name, knew who he was, and who his father was. At the time, he wasn’t sure why, but now he feels sure it was because people could see what a hard worker his father was and admired him for it.

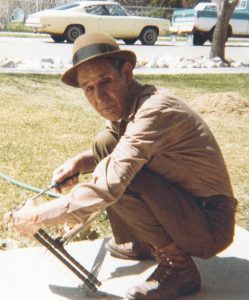

A Loyal Employee and Hard Worker

His dad went to work at Swift and the Stockyards every day for 26 years. He would get up early in the morning, his wife would make him breakfast, coffee and send him on his way with a pack lunch. The cycle was always the same. Sanchez Jr. thinks his dad only missed work about six times over the years he worked there. He had two or three weeks off straight when he contracted a terrible eye infection. He let it go too long (because he didn’t want to miss work) and had to go to the Dee Hospital. Upon arrival, doctors found that he would lose his eye. He had to take some time off to heal and he wore an eye patch for some time and eventually got a glass eye. Sanchez Jr. said his dad accepted it, even though it was a difficult trial. The hardest thing for him to accept was the terrible state of the animal pens when he went back to work! He was frustrated with the careless way they had treated the pens and most likely the animals. It took him weeks to get the pens back into the shape they needed to be in. “To many it was considered a crappy, nasty job, but to him, he took pride in his work,” Sanchez Jr. said of his father. His dad taught him much by example, but also taught him how to work at home. One day he made him mow the lawn three times because he failed to do it the right way the other times. That day, Sanchez Jr. came to understand why his dad spent so much time perfecting his job at Swift – he did it right the first time. On the rare day he had off, they brought in two people to cover his shift.

Literacy, Language and Religious Barriers Lead to Tragedy

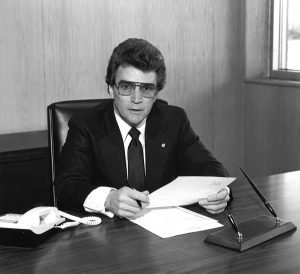

That’s why it was such a mystery when things went south so quickly for his father at Swift. After 26 years of hard work and service, Sanchez Sr. was RIF’d (Reduction in force). Sanchez Sr. was angry and hurt. The problem was that a noticed was posted explaining that a RIF was going to be happening, but Sanchez Sr. was unable to read, leaving him clueless as to the upcoming change. But the part that really stuck with Sanchez Sr. is that those who knew of Sanchez’s Sr.’s difficulty with reading never let him know what was coming. He and six other employees were cut loose, even though Sanchez Sr. was fourth in line seniority-wise. Sanchez Sr. always felt that it was because he didn’t belong to the predominant LDS religion that seemed prevalent at Swift, especially those that worked closely with Sanchez Sr. He always felt they looked down on him and treated him poorly because he was Roman Catholic. Sanchez Jr. said he took his religion very seriously and was proud of it. He felt bitter about the fact that he didn’t feel respected for his religion.

His difficulty with reading was also a struggle his whole life. When he came to Ogden as a young boy, his sister put him in grade school. He was unable to speak or read English and would get whipped with a switch each time he didn’t understand the words the teachers uttered to him. He soon quit school because he just couldn’t take the beating anymore. The language and reading barrier just kept on because he didn’t have the tools to learn to read and speak. He knew quite a bit of English and could respond in English when spoken to, but the reading part was a sticking point for him. But he never blamed his job loss at Swift on his inability to read, he blamed it on those of the LDS faith who he felt didn’t have his back.

Because of the language and reading barrier, Sanchez Sr. made sure his children spoke and read in English, always. They were not allowed to speak or read Spanish, only English. Sanchez Jr. said he knows little Spanish now because of that.

His father found work at a local poultry house, which is also now closed. Sanchez Sr. always loved the work at Swift, though. He loved caring for the animals, even if they were going to die. He loved being outdoors, even though Sanchez Jr. never understood how his dad handled the cold. Sanchez Jr. felt his years at Swift taught him to be a hard worker in all aspects of his life – perfectly groomed yard, shoveled walks, meticulous in all that he did.

His father was struck with Alzheimer’s as he got older, which was tough for the family, but Sanchez Jr. spent his father’s last years with him. When he realized how bad things were getting for his father he moved back to Utah with his wife and family from Houston, Texas to help his mother and father cope with his debilitating illness. Those were not easy times for their family. But now Sanchez Jr. has the memories of his father to hold on to and all those years watching his father work. Sanchez Jr. joined the Army like his father did and it was while he was serving that his father was RIF’d.

Sanchez Jr. still drives around that area, remembering and savoring of his memories of times gone by in the hopping down he grew up in, Ogden, Utah.

Rachel J. trotter

author

Rachel J. Trotter is a senior writer/editor at Evalogue.Life – Tell Your Story. She tells people’s stories and shares hers to encourage others. She loves family storytelling. A graduate of Weber State University, she has had articles featured on LDSLiving.com and Mormon.org. She and her husband Mat have six children and live on the East Bench in Ogden, Utah.

tell your story

Evalogue.Life was hired to capture the history of the Ogden Union Stockyards and the old Swift meat packing plant, including oral history and other research. These vignettes were written by Evalogue.Life team members.