Dallas Casey

Learning to make something from nothing right from the start

Bert Smith’s grandson learns the apple does not fall far from the tree.

Dallas Casey loved the chance he had to help clean out the old Swift Building – memories of his grandpa mixed with his passion for art made for the perfect way to spend his days.

Dallas Casey

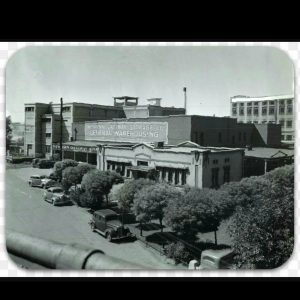

Intrigue. That’s how Dallas Casey has always felt about the old Swift Building that stands just over the 24th Street viaduct in Ogden, Utah. Something about the confluence of the river and railroad tracks converging in the same space always reminded me of something from an old-time movie set in Chicago – a far-away place from the much smaller town of Ogden.

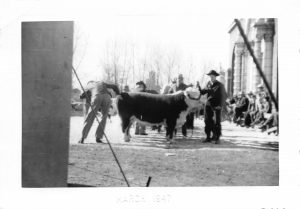

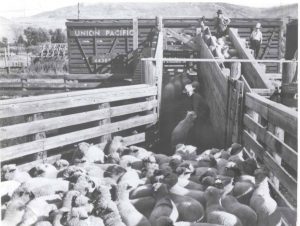

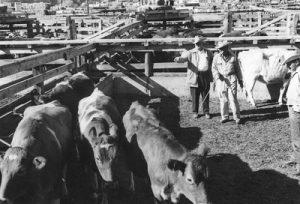

Dallas Casey grew up around the old Ogden Stockyards and Swift Building. He helped his Grandpa Smith clean the Stockyards as a young man, worked at the old Elephant Press as a teenager and then helped clean out the Swift Building as an adult.

Casey always loved the idea of exploring the old Swift Building. Partly because he was intrigued by what might be inside and partly because it was a part of who he was. Casey is the grandson of Bert Smith, owner of Smith and Edwards and many other local and international properties around the world. Smith bought the old Swift building back around the time Casey was born, in the late 1960’s.

As early as Casey could walk and talk Smith and Edwards and even the old Swift Building was a part of his life. His father, Mike Casey, ran the old Smith and Edwards Boat Shop which was located in the old Swift Building for about five years. Casey remembers coming to the shop and being amazed not only by the display of boats, but just the enormity of the building itself. He also loved listening to his dad talk about one if his passions – boating and everything that went along with it. Dallas thought the boat shop fit pretty well in the space, even if it seemed not to. Even in the 1970s the building was in disrepair, but that was okay, it was still pretty cool to him. The boat shop closed when interest rates spiked, the old viaduct was torn down and gas prices spiked sky high.

But Dallas’ interest with the real estate didn’t go away. One of his church leaders, Ron Hirschi ran the Elephant Press out of the south west side of the old building and Dallas spent many a day down at the press because he liked Hirschi but was also best friends with one of Hirschi’s sons. Hirschi rented the space from Dallas’ grandpa and he liked the idea of being in a place that his grandpa owned, with his friends. Graffiti was a common occurrence at the Elephant Press site and really many places at the building. One particular time Dallas was with friends down at the press and they thought it would be funny to do the graffiti themselves to play a trick on Hirschi. They took a few photos and called him and told him what they had done. They spent some time cleaning graffiti whether it was of their own doing or someone else’s, so why not have some fun in the process? It was during that time spent at Elephant Press that Dallas’ fondness for the area increased.

After Dallas left on his LDS Mission Hirschi sold the business and a business called Mobile Sound moved into the space, but that space wasn’t long for the location either.

But while Dallas spent time at the Elephant press, the rest of the place was off-limits and a bit mysterious. Sure, he would come with his grandpa to drop stuff off in the Swift part of the building from time to time – old boxes, excess surplus, things of that nature. His grandpa didn’t ever say much about it when they stopped in, but it was a mystery Dallas felt a nudge to explore…someday.

Sometimes he would have friends make the suggestion to sneak in to the old place – lots of teens did it in the 1980s and 1990s. It was a kind of “safe danger” to lots of kids. Could they sneak in without getting caught? What would happen if they got caught? Better yet, could they get on the roof without being detected? What about throwing rocks inside? All these things were questioned many a rebellious teen wanted to explore during Dallas’ teenage years. But, for Dallas, that was a risk he would never be taking. He didn’t even want to know when or if any of his friends had ever made that adventure. “Don’t tell me you’re sneaking in there. I would rather the cops came than my grandpa!” Dallas always told friends and even acquaintances. Letting down or disappointing Bert Smith was not something high on the list of Dallas Casey. “I was always more scared of grandpa than anyone else. I don’t know why, but I didn’t want him mad or disappointed in me,” Dallas said with a grin. Dallas did go in once when working with someone on a family project – either taking a load in or a load out, he doesn’t remember, but he got to ride the elevator. It was creepy to say the least. He tried to take it in quickly, but now doesn’t even remember what he saw.

As Dallas got a bit older, so did his grandpa. He started to spend some time with him clearing out the stockyards, which are just west of the Swift Building. Smith owned some of that property as well and he always needed help going through surplus and clearing things out. They would have some good talks and there were times when Smith was very frank and direct with Dallas, even a time or two when he got a little agitated with some surplus items that Dallas thought was garbage and he got rid of. As they worked, Dallas would often ask him how he decides what is worthwhile material and what is not. Dallas loved to listen to his philosophies and ideas. One of the things Dallas came to love about those conversations with his grandpa is that he came to realize his talent of seeing potential in all things. This is something Dallas came to realize he and his grandpa had in common, which seems odd, considering how different their personalities are. “I can see potential in things for art and creating. Grandpa could see potential to help others too, but could also see the financial side,” Dallas said, shaking his head at the memory. Dallas is an artist by nature and has spent some of his career as an artist, pretty much the opposite of his grandpa, but the two could find common ground with surplus. As the two would work in the Stockyards during the twilight of Smith’s life, Dallas also got to see a different side of his grandpa. Friends would stop in and do and say different things and he would see his grandpa be a friend – laughing and joking with people. Not something Dallas always got to see. “He always held his cards close to the vest with us (grandchildren) and we didn’t always see that. I’m so glad I got to see it here,” Dallas said of his stockyard time. Then he had no idea the connection he would get to feel with his grandpa or all the other stuff he would be seeing over the next few years.

But as Dallas worked at the Stockyards with Smith, the idea of getting inside the Swift Building started looming larger for him. What was inside? There were urban legends for sure. Maybe crated Jeeps, motorcycles, maybe even an old-timer Harley Davidson Motorcycle was somewhere in a dark and forgotten space.

When Dallas’ grandpa died it also coincided with Ogden City’s plans to buy the Swift Building and the surrounding areas and develop it into green space and some different things. But before the exchange could happen there was lots of clean-up to do. But there were also some changes in the family business. Dallas’ cousin Craig Smith was now the CEO. Dallas’ father, Mike Casey who had been a vice president had retired before Bert Smith passed away and Jim Smith, Bert’s son had passed away a few years before as well. Different family members were doing a variety of things, including Brian Opheikens who was married to another of Dallas’ cousins. Craig Smith approached Dallas about being the surplus manager now that Bert was no longer with them. For Dallas that was just too much. “I thought I could fold under the pressure,” Dallas said of such a large job. Not because he wasn’t fully capable, but because it was family and he didn’t want to have contention or let anyone down. “I didn’t want to butt heads and I could see that would maybe happen. I wanted none of that,” Dallas said. He turned that job down and kept working at his job at Jim Alvey Productions.

As things continued to shift, Opheikens was asked to start doing some work at Swift. Dallas knew he was a pretty good scrapper and salvager. He was a hard worker and had an eye for a good deal and also knew how to clean things out. This was reassuring for Dallas. Dallas continued working for Jim Alvey but was feeling the pull to go down to Swift and check things out. Dallas spoke with Brian and said he would like to help, Brian was more than open to the idea, so Dallas started working alongside Brian. The two were working side by side, but both Brian and Dallas could work alone too. They started loading out freight and lots and lots of army surplus along with cleaning supplies that were all send to Smith and Edwards. Dallas found that he enjoyed working with someone, but it was hard work, day after day. But hard work can be rewarding and this definitely was for him.

When they first started they invited some local “pickers and scrappers” to come and check things out. “It was mostly people we knew and it was a private invite only affair,” Dallas said. “Things started going like gangbusters. People would come picking and it was nice because we could all trust each other,” Dallas said. It was normal for different pickers to be going through stuff and exclaim, “Come check this out!” and everyone would come running to see the latest find. Because they were all different experts in different things, it wasn’t uncommon for them to share value of items or quickly look it up on google or another “picking” site to see values for items.

And while Dallas never found a crated Jeep or Harley Davidson motorcycles, there were some treasures to behold. Because of Dallas’ artistic knowledge, he knew a bit about architecture and architectural finds. When he first started cleaning out the building molded plywood leg splints designed by brothers Charles and Ray Eames, were extremely popular and going for big bucks – around $500 a piece. They were mid-century modern and quite beautiful. People were finding them at garage sales and selling them for a high price tag. Those who bought them would hang them on their walls as an eclectic art piece.

As Dallas ventured into a particularly spooky room one day he almost didn’t go in. As he opened the door he could see row after row of army rain coats hanging on long pipes. It was dark and almost looked as if soldiers could be standing in the coats the way the darkness cast across the room. They were hanging in rows and pretty much covered the space of the room. There was also 4” of water on the floor in the room. But there was something pulling Dallas into the room and he had to check it out. He landed on his reason for venturing in. A huge stack of molded plywood leg splints! Before he knew it, he was yelling and screaming, expletives flying out of his mouth. “Come quick, come see what I’ve found,” Dallas yelled, laughing and clapping as he got closer to the stack. There were 17 to 20 of them, just sitting there. Dallas worked quickly to pull them out of the stack to see what shape they were in – the shape was decent and he could fix them up perfectly. He called his friend and local art expert Ron Green. “That’s cool,” he said with some excitement, not quite as much as Dallas had hoped for. “Hold on to them. The market has dropped,” Green added. But Dallas wasn’t too crestfallen. For him, it was a goldmine find that he feels confident will turn into something great at some point. For now, he has some super cool art pieces in his own living room. “It was so fun to find something elusive,” he said, still grinning and laughing at the moment.

There were also the quirky things they discovered that had nothing to do with treasure. Take the boiler/engine room, for instance. Dallas and Opheikens started picking up rocks they would see in there every time they went in. At first there were river rocks everywhere. After seeing the rocks everywhere, they looked up at the windows. “That’s 40 years of people throwing rocks at the windows,” Dallas said. One of Dallas’ first thoughts about it was, “how lame.” But then when got thinking about it he realized each rock represents someone stopping to pick it up and throw it at the window. Now the rocks sit piled up where Dallas and Opheikens piled them nicely upon visiting the big, open room that once was a vital part of the old building.

For Dallas, the potential for use he would see every day was exciting. “There were so many springs and bolts that could be used for projects. They were often even already sealed in plastic bags,” Dallas said. But even if they weren’t, Dallas felt obligated to grab them and think of what they could be used for or how they could make a task easier. There have been thousands of things like that, but they can be hard to sell, especially in small places and small ways.

Dallas had spent his life seeing things with potential and this place truly inspired his creativity. “I am just fascinated with it,” he said as he looked at the old Swift Building.

Rachel J. trotter

author

Rachel J. Trotter is a senior writer/editor at Evalogue.Life – Tell Your Story. She tells people’s stories and shares hers to encourage others. She loves family storytelling. A graduate of Weber State University, she has had articles featured on LDSLiving.com and Mormon.org. She and her husband Mat have six children and live on the East Bench in Ogden, Utah.

tell your story

Evalogue.Life was hired to capture the history of the Ogden Union Stockyards and the old Swift meat packing plant, including oral history and other research. These vignettes were written by Evalogue.Life team members.