Brian Opheikens

Grandson-in-law to Swift Property Owner Cleans Things Out – A Labor of Love

Getting Things Ready for a New Birth

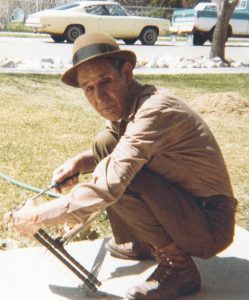

Brian Opheikens loves looking through old things for great artifacts to keep or re-sell. His love for all things old has kept him very busy the last couple of years.

Brian Opheikens

Brian Opheikens always had a special affinity for Bert Smith after he married his granddaughter about 10 years ago. He loved his ability to make something from nothing by the world’s standards, but for Opheikens, he could see that Bert could just see things for what they really were. And why? Opheikens thinks the same way.

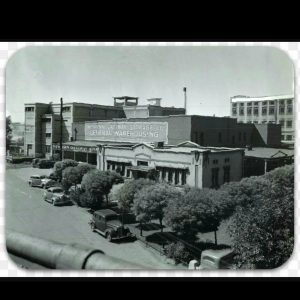

Brian Opheikens dreamed for years of getting inside the old Swift Building. When that dream became a reality he learned much about himself, his family and Weber County.

A Love of Scrapping

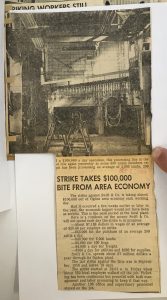

He started scrapping things like metal with his good friend Carson several years ago and he had always had his eye on the Swift Building which he knew Smith owned. At family functions Opheikens would often try to get Smith’s ear to see if he could get in there just to see what was in there. Not necessarily to scrap anything, but just to check it out. “It was always no, no, no from Bert for a long time,” Opheikens remembers. His friend Carson kept at him about the prospect of checking the building out though.

A Sneak Peak

Smith finally let him on the grounds around the outside and Opheikens looked around, taking it all in, and started to work to clean things up. What he saw there was a lot of potential, but also a lot of trash and a lot of potential work. About two years ago, just before Smith passed away they wanted to start to assess what was on the property and wanted to start with the Industrial Supply portion of the property. Knowing his love of scrapping and that he wasn’t afraid of hard work, Smith contacted Opheikens and Bert’s other grandson, Dallas Casey. Opheikens had been doing some work at Smith and Edwards and so a deal was made to use some of the things in the Swift building for Smith and Edwards. At first, Smith and Edwards was going to buy it all. They thought they could make quite a bit of money from what was in there, but they didn’t really know what was in there either. The family was a little skeptical too, because they didn’t want to lose too much if they created a deal to sell it all. So, a contract was created and Opheikens worked directly with the store – they could buy and purchase what they wanted and Opheikens and his group could also “scrap” other items. Opheikens and his friend, along with Dallas seemed to think the deal would work. And it has all along. “There really wasn’t an issue about it and it has worked out fine although I stayed out of the logistics of it. I just let Craig handle it,” Opheikens said. Craig Smith is Bert Smith’s grandson who know runs Smith and Edwards.

They started in the Industrial Research arm of the building and there was a treasure trove of cleaning supplies there that the store used and did well with, Opheikens said. As for the main building, Opheikens had no idea what he would find when he entered. “I had heard rumors and I was excited, but I was also afraid of Lother,” Opheikens said of the first few visits. Lother was the caretaker of sorts for the property. An older German man who is very rough around the edges. At one time he worked at Smith and Edwards, but Smith had hired him to keep an eye on things at Swift and he took the job very seriously. He was also slate as a mechanic on the property, fixing forklifts and what not. A side note to his caretaker job came some hoarding of some of the items from the building. He felt very possessive of the property. There were times when Opheikens would come down and Lother was a bit confrontational with him which Opheikens didn’t like. Opheikens doesn’t think that Lother had any bad intentions and there were no major contentions, but some minor ones and some bumps along the road. Opheikens would ever know what he was going to get when he saw Lother. “He was just straight up rude,” Opheikens said. Opheikens tried hard to work him and admitted he really tried kissing his butt a few times, and this was when Opheikens was still working on the outside of the building. Lother kept harassing Opheikens enough that he felt frustrated. Smith caught wind of this and wrote a letter to Lother telling him to knock it off. “It was really quite sweet. I cherish it. The note really backed me up,” Opheikens said. From then on, there have still been moments of frustration and contention, but Lother backed off from Opheikens quite a bit. “He thought I was a threat for no reason,” Opheikens said.

Seeing Inside Swift for the First Time

After some of those difficulties were resolved, Opheikens finally got his dream day – his day to go in the doors of the Swift Building and to see what was really there. Smith had passed, so it was Craig and some of the other Smith and Edwards crew that accompanied Opheikens on the walk through.

Opheikens felt like a kid on Christmas as he walked through the doors, but that Christmas morning feeling didn’t last long. Sure, there was PLENTY of stuff in there, but it wasn’t the finds he was dreaming of. “It’s like thinking your’re going to find $1 million and you find $100,000,” Opheikens said. “Now there was good stuff, don’t get me wrong and we have done well with it, but it just wasn’t all that I thought it would be,” he added. Soon after the initial walk through Smith passed away, but the work has continued. Initially there were some trailers full of items that the store was able to use.

Keeping Watch

Security also became a big part of the job. “For a long time people were just coming down here and talking whatever,” Opheikens said. Opheikens and Casey starting working really hard at keeping people out. When they first started coming down and working on the property they would do a walk through to see who was on the property, or if anyone was. Those were some scary moments for Opheikens. One time he ran into a Hispanic family in between the Swift building and the Industrial Supply building. There were four kids around the ages of teen and tweens. They startled Opheikens and he didn’t know what to do with them once he caught them, but he decided to call the police. Once the police came down, they seemed familiar with the family and they called the mom. The oldest boy said he had left some items on the property and had come to retrieve them. “He wasn’t ignorant at all, he was very polite,” Opheikens said. The mother, Opheikens and the police officer came to an agreement about the trespassing and the kids said they wouldn’t be on the property again. He hasn’t seen them since.

Another time, Opheiken was on the property early on a Saturday morning. He was in the Industrial Supply Building again and he saw a very young girl, about 15. “She was dressed real nice, not like she was homeless or anything. She had some nice flip flops on and a tank top,” Opheikens recalled. I looked at her, asked her if she was okay and she ran off. “It kind of scared me,” Opheikens said. “Sometimes I ask myself it was a ghost or something, but I’ve never seen again and I really hope she was okay,” Opheikens said. There have been quite a few run ins with homeless people as well. Many more when Opheikens first started working there than now.

Figuring it Out

Opheikens said those first few months were a bit tedious for he and Casey. “We didn’t know what we could and couldn’t sell and we didn’t want things to be uncomfortable with Kathy (Smith’s widow,)” Opheikens said. Opheikens had a great talk with Kathy and she told him she trusted he and Casey and kind of gave them some wiggle room, well maybe a lot of wiggle room. “She told me she knew the doors weren’t going to walk off. I really appreciated that about her. She has been so kind and so easy to work with. I just can’t tell you how much that has meant to me,” Opheikens said.

Opheikens has enjoyed working with the Smith family in general. He has seen the transition since Bert has passed away as a smooth one, with both Kathy and Craig being very cordial to each other and other business partners, including Opheikens and Casey. Opheikens credits a big part of that smooth transition between he and Kathy to the fact that she can rest easy knowing that the safety concern has been cut down significantly. Opheikens knows it’s good for homeless people or other vagabonds to know there are people there on almost a daily basis so they can’t be hanging out there. They also installed video cameras, which Opheikens attributes as a big secret to deterrence on crime there. “People see those cameras and they don’t want to be on them,” Opheikens said with a laugh.

“I’m not afraid of a homeless person though. I am afraid of scary people with weapons – a knife, a gun, a tight encounter,” Opheikens said as he looked around the building. “The longer I’ve been coming down here the less afraid I am. Most people just take off running when they see us,” he said. But he still stays careful. “You could make one homeless mad and stir up a hornet’s nest,” he said with a big grin.

Cool Finds

But he also doesn’t let that deter him from the work at hand and all the interesting finds he has made at the building. One of his favorites? An old-time soda machine. He did a bit of searching on the Internet to see what its value could be and he found out he may have hit it big. It was a 7-Up machine, but the first of its kind – but there was one catch – it has the sign had to be made by Royal Crown. If it was, he had hit the “mother load” and it would have been worth up in the area of $10,000. But alas, it was from RC Cola. But, still super cool and worth about $4,000.

“People are always asking me if I’ve found any gold here,” Opheikens said with a big chuckle. “I haven’t and if it was here, they did a pretty good job of hiding it,” Opheikens said.

Two years has passed since Opheikens started pouring his heart and soul into the “Swift” operation. As he talked about the experience he sat on the dock portion of what was once the Industrial Supply portion of the property. He lovingly refers to the space as his “office.” He sat on a broken office chair and spread an old towel on an old-time school desk to conduct the interview. The area is littered with remnants of years gone by – nuts and bolts, old cups, smashed soda cans, old clock parts – all pieces of people’s lives when they worked the place, either when it was a meat-packing plant, a cleaning supply spot or even way back when it served as a refrigeration site for the animals slaughtered in the Swift Building adjacent to the space.

It’s hard to imagine what things looked like before Opheikens and Casey got started there just because there is so much stuff everywhere. But there is much less stuff than their used to be and Opheikens has learned what is in the space, where it is and what most of it is worth.

As he walks through, carefully guiding those eager to see just what sits within the walls of the old places, he points out old army helmets and then with the next step a skeleton of a raccoon. One afternoon we happened upon to raccoons fighting. We cleared the space fast, but Opheikens stuck around for just a minute, making sure all was well before he cleared the area. He shows off all the old soda cans he has collected over time – a long line of cans that display much history of the space – Old rootbeer, 7-up, RC Cola and just some old Coke cans. Those cans give a glimpse of the history the place has seen. Opheikens admits he get pretty excited when he comes across the cans because it gives him some insight into the history that is there.

He excitedly showed off an old magazine ad he found in the old Swift bathroom near the “kill floor” when he lifted an old mirror. “It was probably something pretty bad for the time,” Opheikens said as he pointed out some naked ladies – not in sexy positions or anything, but just there. “Pretty tame for our day, but I thought it was pretty funny,” Opheikens said with a little laugh.

Working With the Pickers

Opheikens has learned how to be a good judge of other pickers as they have come along and wanted to grab some of the memorabilia there. There have been some people willing to pay a fair price for items, and others not so much. Opheikens has had to evaluate that and make sure people are on the up and up and then figure out how to let them know they aren’t welcome back, not always an easy job. But he has made some good friends with some who are there for the right reasons. Some “pickers” come on a Saturday morning, take a peruse through the building and stack things up on the dock of the big bays on the south end of the Swift building. Opheikens has enjoyed seeing what “one man’s treasure” may be because he has found that it’s different for everyone.

There are still layers and layers of things to recover, but time is running out. Great finds still surface on the daily though. Just the other day he found a set of stamps that meat packers would stamp on Swift meat packages before sending them out. There were 10 or 20. He lined them up and examined them carefully. The stamps, like many other things, show the different ages things were happening when Swift was opened. Different kinds of logos, different names under the Swift name. And while cool finds are still within the walls, Opheikens feels pretty good that the best stuff has been retrieved though. “At the end of the day I feel pretty good about how things have turned out,” he said.

Rachel J. trotter

author

Rachel J. Trotter is a senior writer/editor at Evalogue.Life – Tell Your Story. She tells people’s stories and shares hers to encourage others. She loves family storytelling. A graduate of Weber State University, she has had articles featured on LDSLiving.com and Mormon.org. She and her husband Mat have six children and live on the East Bench in Ogden, Utah.

tell your story

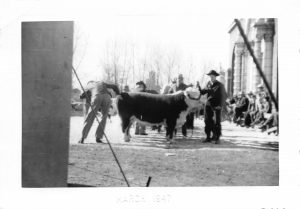

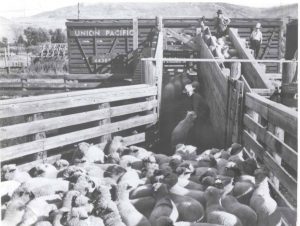

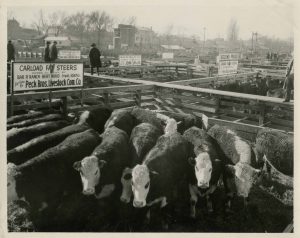

Evalogue.Life was hired to capture the history of the Ogden Union Stockyards and the old Swift meat packing plant, including oral history and other research. These vignettes were written by Evalogue.Life team members.