Verl Thompson

Farm Boy to Big City Meat Packer

Working on a farm wasn’t for Verl Thompson, he wanted something more

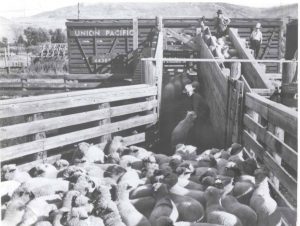

The 1950s were a hopping time in the Ogden Stockyards/Swift Meat Packing Plant. And Verl Thompson was in on all the action.

Verl Thompson

There’s not much work to be found in Lewiston, Idaho. Not much work unless you want to be a farmer. And that wasn’t the line of work Ivan “Verl” Thompson loved to do. He did it long enough, but after his LDS mission, he knew it wasn’t his life’s work. Plus, he wanted to make some good money so when the time came, he could provide for his family.

Verl Thompson never minded getting his hands dirty or working in the cold Swift Meat Packing Plant. He had goals and he knew Swift was the place to make them happen.

A Chance for a Leg up in Life

He caught wind that there was a meat-packing plant in Ogden that paid well and decided he would give it a try. “I needed a job and heard there was some butcher work,” Thompson said. He decided to try it and that he would take the time to commute the 60 miles to the job. That didn’t last long though. The commute proved to be too much, so Thompson decided he would re-locate to the bustling junction town.

The year was 1952 and things were hopping at Swift. He was hired on to work in the cooler. He was there to greet the dead cattle soon after they were slaughtered so they could be cooled in preparation to be cut. The place was cold. “It was cold, but I didn’t pay it much mind,” Thompson said with a laugh. “They had to keep the whole place cold so the meat wouldn’t spoil so we just got used to it,” Thompson said, thinking of the memory. He wore a big, heavy shirt and coveralls in all parts of the plant that he figures employed about 100. “I stayed pretty warm, really,” he remembered. Even though the plant was kept at a toasty 35 to 36 degrees, he remembers.

Working in the Cold

When he worked in the cold room the meat would come there directly from the kill floor which was essentially the top floor of the plant. From there the meat would need to cooled before it could be butchered. At first, Thompson spent his days there, getting the meat cool and hauling it around. He remembers it was physical work, but because of his young age he didn’t think much about it. They would arrange it to go to the different parts of the plant depending on the meat. He worked primarily with the cattle and sheep and had little to do with the pigs, that was pretty much in a different space from Thompson’s memory.

He didn’t spend a lot of time working in the cold room before he was promoted to butcher. There he would cut up the cattle into fairly large pieces to be transported out to grocery stores – and mostly local grocery stores at that. They would ship some out, but most of it stayed in the area. He cut it into bigger pieces and the grocery stores could then cut the meat how they liked it to get the best sale. Thompson found that most of the stores liked to do it different. “I got of a lot of lessons in cutting meat, but it wasn’t very complicated, but it was hard work,” Thompson said. Thompson was paid by the hour, unlike those that were “meat boners” who turned the meat into hamburger. Alberton’s was one of their biggest orders. “Their orders were big and I never wanted to do those when they came in,” he said with a sly smile. He did though because he liked the idea of working hard. He knows some of the meat was shipped out on rail cars, although he didn’t ever think it was a whole lot. “It may have been, I just don’t remember it that way,” he said.

A Natural Butcher

He also never lost the knack for being able to cut meat. He was always the designated cutter when they would get a deer. “I would take it home, cut it up, put in a locker and give it all away,” he said. But cutting meat never made his stomach turn. He has always been able to eat the meat in spite of those 19 years of chopping it up. “It didn’t bother me. I saw it raw and I knew what it was,” he added.

Thompson usually worked an 8-hour shift, unless there were extra orders to be filled. If that was the case his 8-hour day would quickly turn into a 10 or 11-hour day but the time went quickly because he was busy. If the worked 10 hours, Swift was always careful to feed the employees. “They sent us to a café for dinner,” Thompson said. The café was located in west Ogden out of the Stockyards. He didn’t remember a lot of the details of the place, but does remember he was pretty thrilled to get a free meal and paid extra for extra hours of work.

Friends, But Only at Work

He had a few friends that he was chummy with at work, but that ended, for most part when he punched the time clock. “There were a lot of good guys there. I really liked them, but we did have a lot of different values,” he said with a laugh and grin. Thompson didn’t enter in with a lot of the after-work shenanigans, but he liked the men while they were on the clock. Thompson admitted he was a family man and not long after he started working at Swift he got married and started his family. He was interested in getting home to his wife.

Thompson mostly worked with the beef, but if he got done with the orders on the beef he would move over to sheep area and help there. He didn’t do that a whole lot and doesn’t have a lot of memories of what he did while in that department. He did like the fact that everyone did pitch in and help though. If one department got done with its work, they moved to another department and helped each other out. Sometimes the job could get monotonous – hours and hours of cutting, but that was only when it was slow and they were waiting for orders to come in. “But we were busy most of the time,” he noted. He didn’t mind the times he could help with the “lambs” as he called them as that department always seemed to be thriving and busy.

As long as he worked there he made an hourly wage and didn’t know of people who were paid by the sheer amount of work they completed during the time, although some accounts have said they were paid by the number of pounds they cut, or ground up into beef. “That was not in my department,” he said. One thing he enjoyed was the fact that the employees all worked hard though. No one slacked off and were eager to get the job done, for the most part.

They Treated us “Pretty Good”

“They treated us pretty good,” Thompson said of the management at Swift. He didn’t feel put upon by them or underappreciated. “I really felt like we was government workers in a lot of way, by the way they treated us,” Thompson said of the place. The upper management seemed to like all the workers and didn’t want to see a lot of turnover so they treated the employees well. “For me, it was a good company to work for,” Thompson said. Although he is quick to say the very best part of the job was always payday. Talking about payday yielded the biggest grin of the day from Thompson, who is now 92. “They paid us real good,” he said.

Rachel J. trotter

author

Rachel J. Trotter is a senior writer/editor at Evalogue.Life – Tell Your Story. She tells people’s stories and shares hers to encourage others. She loves family storytelling. A graduate of Weber State University, she has had articles featured on LDSLiving.com and Mormon.org. She and her husband Mat have six children and live on the East Bench in Ogden, Utah.

tell your story

Evalogue.Life was hired to capture the history of the Ogden Union Stockyards and the old Swift meat packing plant, including oral history and other research. These vignettes were written by Evalogue.Life team members.