Rillon Champneys

Rillon Champneys grew up quickly from the things he saw at Swift

No regrets, but a lover of hard work

Rillon Champneys learned how to work hard and stay happy working on infamous “kill floor” at Swift.

Rillon Champneys

Rillon Champneys wasn’t quite 18 when he started working at Swift. The technical age was 18, but it seemed to be something the bosses there quietly looked the other way about from time to time. Champneys was one of the lucky ones in his case. He started working at Swift the summer of 1950. Since he was still in high school, Swift was a summer-only job for him. He doesn’t remember exactly where he started, but he quickly ended up on the kill floor.

It didn’t take long for Rillon Champneys to notice one thing most of the workers on the “kill floor” had in common: They were all unhappy.

The kill floor was where all the animals were slaughtered and for Champneys, it was not a place of happiness and joy. “On the killing floor people were unhappy all the time,” Champneys recalled. The work was hard and fast-paced. For Champneys, making friends wasn’t an option because there simply wasn’t time. He never even took a coffee break on the days on the killing floor. He knew guys on other floors made friends, but there was just no time on top and it was pretty cut throat. He worked between 10 and 12-hour days, but sometimes 14 hours. He made around $12 per day, which was big money for a high school kid.

The Kill Floor

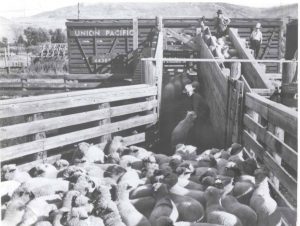

Champneys mostly focused on killing sheep and he figured about 6,000 went through per day. “Good Lord, I wouldn’t have wanted to work there all the time,” Champneys said of his summer job. For him, working on the kill floor full time, all year would have been a bit too much. He would often think that the outside world just didn’t understand what it was like to work on the kill floor. As he worked he could see that it would get to people and some would lose their sanity. Granted, he didn’t know what their home lives were like that may have contributed to the sadness and anger, but he also could see that the fast pace of the work and the constant need to be faster and better would get the best of nearly everyone. If you didn’t keep pace (or beat pace) there were plenty of people waiting to take your job. The killing floor jobs were the highest paying jobs and plenty of people were vying for them – hoping someone would mess up so they could take the next man’s spot. Champney’s didn’t worry too much about it because he knew it was a summertime job – a means to an end and he could also see what working there year-round did to a man’s mental health and he didn’t want that. But…he really liked the money and for him it was the only positive thing about working there.

Killing the Sheep

There were different kinds of jobs to be done on the kill floor. Because there was a belt-like chain drive whatever job you had you had to keep things going at high momentum. The shifts were in 10 to 12-hour increments and none of the kill floor jobs were easy ones – and even when Champneys tried to make extra money with other side jobs there, they were taxing as well. “Everything was blood and guts (on the kill floor),” Champneys explained. He would find it hard to eat lunch on his lunch break because there was so much blood everywhere it would often make his stomach upset. “Sometimes it would take me three days to eat my lunch,” he noted, just because it was hard to get his stomach settled on a daily basis. He would often trade off on jobs on the floor because he was young and willing to do what needed to be done. He always was equipped with his apron and knife belt that he would wear over his regular clothes. For him, when he started working there all the blood was hard for him to take and even when he wasn’t eating the smell and the thought of the blood was a struggle for him. “I had to get my stomach all straightened out,” he said. “There was blood everywhere, all over the floors, all over the counters, just everywhere. It was hard to believe at times,” he said of the condition of the place during the busiest times. As for the jobs, there was the header who would get rid of the last bit of wool on the sheep. Then there was the cleaner. Somehow the sheep would get very dirty on their rear ends and they would have to be cleaned before they could be slaughtered. They would then shackle the sheep and hook them onto the big, heavy chains and one of the workers would cut their throat, hence all the blood that Champneys came to hate so much.

Then before they could go in the freezer they would have to be pinned on their hind and front legs. Their legs would be wrapped with little sticks with very sharp ends points. The government inspector would then stamp their rear ends once it was complete. It was particularly tough in the summer because it was hot outside, but they had to keep it cold inside. The person in charge of the temperature would often get into trouble because he would struggle to keep the temperature cool enough during summer months.

Killing the Pigs

Champneys also worked at killing the pigs. “Those pigs were so big, good Lord,” Champneys said with a big sigh. Before they could start the slaughter, they would have to take two little parts like pellets off the back of the pig. “We would get the pig, open him up with all the guts and there were two layers. We would peel the fat off – two peels and we would have to find those two dark pill shape things about an inch long and a quarter inch in diameters. They never told us what they for and I always wondered that,” Champneys said. Once they found them they would cut the pigs throat and throw it in a boiling tank of water. It was a huge round tank, but just before they would throw then in they would have to shave off their hair. “It was kind of pitiful,” Champneys said.

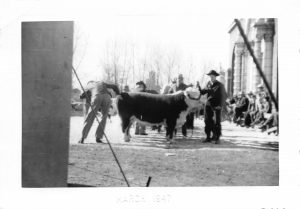

Cow on the Loose

One day while everyone was slaughtering like crazy, one of the cows decided he wasn’t going to the slaughter. They would kill the cows with a sledgehammer as they came in and put them in the shoot. But one afternoon, they didn’t get the cow knocked out all the way and he got out free on the kill floor. “He was crazy!” Champneys exclaimed. “He took off running through there and knocked everything off the ceiling. The floor was slick, so when he tried to charge he couldn’t go anywhere because it was so slick,” Champneys added. Men started running off the floor as fast as they could because they cow was mad. But as the men they slipped too because it was so slick. In a way, it was a scene of panic, but also hilarity, because no one could move, but the cow was still coming after them. “Once he started charging he just tore the hell out of everything,” Champneys said. But, luckily because it was slick, he couldn’t get a lot of momentum. One of the workers came from out of nowhere and just shot the cow dead. “It was one of the funniest things that ever happened,” Champneys said with a laugh at the thought.

Extra Work

Some days when all the slaughtering was done they would ask some guys to stay and do extra work. That usually entailed taking the pelt off the sheep. Once the pelt was off he would drop it down a chute onto a lower floor. He would then go down to the lower floor and take the pelts and put salt on them. After about four dozen were complete, he would shake the salt out and put into a box for shipping. There were what seemed like thousands of pelts to be done at a time and four men would work with them at once. Why salt? Champneys wondered that for a bit too, but it was then explained to him that the salt would keep the hide soft. When he handled them the pelts still felt soft to him, but they would slowly get hard even as the day would progress – they would be hard enough to be able to shake the salts off. He always felt so tired trying to get all the salts off after working so hard on the killing floor. Even though it was some extra money, he always questioned if it was worth because his body was always so physically exhausted.

Dealing with the crazy

Some of the hardest and saddest parts of the job for Champneys was to watch some of the guys go crazy, literally. He watched two men take their own lives while he was on shift. One man cut his wrists and another jumped off the platform and landed on his head. Several others threatened to jump as well. Champneys was always troubled but what he saw, but also see why the men were driven to it because of the stress of the job. People were afraid of losing their jobs, making quotas and it was simply unpleasant on the kill floor.

All About the Money

“It was a horrible job but it paid really good money,” Champneys said. “I bought a car and good clothes,” Champneys said. It was for that reason that he considered trying to get hired on permanently after he graduated from high school. He had finished his senior year and hadn’t been working at Swift for a few months when he approached his mom about going back to Swift. “It took me six months to get the smell out of your clothes from the last time!” she exclaimed, shaking her head. “That job made you so tired,” his mom reminded him. That was true. He would come home after work and collapse in the kitchen chair just inside the back door every day after his work on the kill floor. The memory of the terrible smell and the hard work rushed back as his mom reminded him, but the money was calling his name. So, he decided to go back anyway. They quickly hired him back (he never knew why they liked him so much except for the fact that he always worked hard and didn’t talk much.) But by the time he got home from his first shift, his parents had something else in mind. They didn’t like the way he acted or felt after his shifts at Swift so his father found him working on the railroad –another hard-working job, but less stressful. He spent the next 23 years of his life working on the railroad. “There was no other job like that, that’s for sure. I can’t think of anything I’ve ever done that ever came close to working on the killing floor,” Champneys said of his time there. He was glad he did the job, he liked the money he made, but it also taught him what kind of work he didn’t want to do for his whole life. Good life lessons learned for Rillon Champneys.

Rachel J. trotter

author

Rachel J. Trotter is a senior writer/editor at Evalogue.Life – Tell Your Story. She tells people’s stories and shares hers to encourage others. She loves family storytelling. A graduate of Weber State University, she has had articles featured on LDSLiving.com and Mormon.org. She and her husband Mat have six children and live on the East Bench in Ogden, Utah.

tell your story

Evalogue.Life was hired to capture the history of the Ogden Union Stockyards and the old Swift meat packing plant, including oral history and other research. These vignettes were written by Evalogue.Life team members.