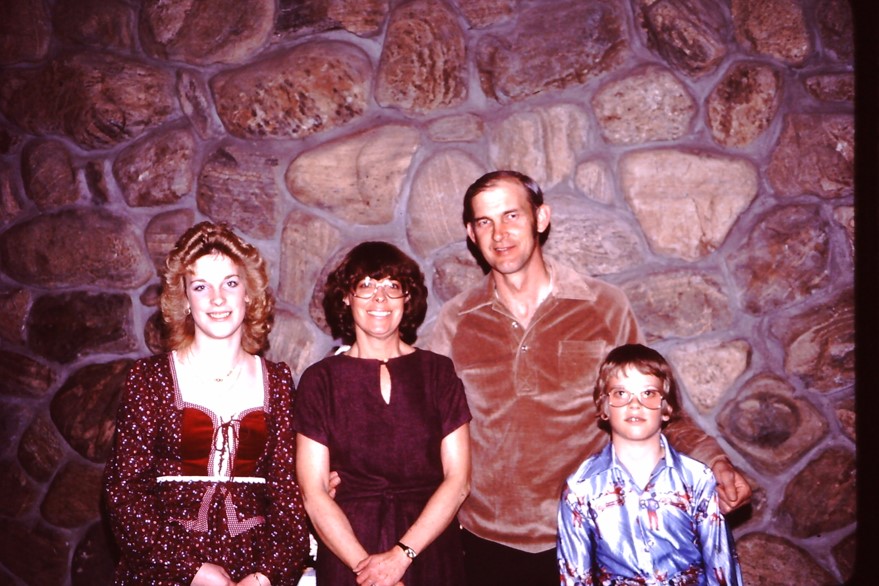

Wayne Vandersteen

Wayne Vandersteen Grew Up Quick at Swift

Young man learns about hard knocks of life

Wayne Vandersteen took good care of his tools and everything about his job at Swift. His family was depending on him.

Wayne Vandersteen

Wayne Vandersteen was the ripe old age of 16 when he started working at Swift in 1949. “I wasn’t supposed to be there, but I did it anyway,” Wayne said with a sly smile about his young age.

He started off cleaning the floors, but that only lasted one day. They threw him into the pork boning department on his second day. The pork and beef boning were in the same area, but different rooms. Wayne would get the pork after it had come off the belt gun and had to bone it quickly.

Wayne Vandersteen took his job very seriously, but when things got tough at home, he had to stand up for his family.

A Master at the Craft

Wayne got so he could bone four or five pigs per shift. Wayne liked the jobs, but accidents did happen. One guy cut his stomach open on the belt cutter. “It was pretty bad, but accidents happened, it was part of it,” Wayne said. Wayne could see there was more money to be made in the beef boning area and so he worked hard to get moved over there. He loved the fact that he could make more if he worked harder and boned more beef. For him, it was always a challenge and competition with himself every day to do a little better than the day before – make a bit more money. “We had to make the standard. Once we did that everything was extra,” Wayne said. The standard was to bone two cows in one hour. Wayne could sometimes do three or four on a good day. Thousands went through there in a week. He never thought of the job as hard at the time, but he did have to work hard. Once he learned a new trade, it wasn’t hard. “I never seen anything in there that was hard,” he said with a laugh.

He wore all own clothes to work and was given a set of knives for the job. They were his to take and forth to work each day. Wayne treated his tools with the utmost care, sharpening them regularly and making sure they were in tip-top shape. “The sharper your knives, the faster you could go, you see,” Wayne said at the memory. One day they would cut the beef to prepare it for hamburger and then another day they would cut the meet in different parts. They would cut the hind quarter into steaks and the and the front quarter into hamburger. On hamburger days, they would take the meat for hamburger to a different area to be ground. When he worked with the pork they did a similar procedure with the pork to make hot dogs, but they always called them weenies, Wayne remembers. There was some work done with sheep as well – some of the lamb was ground for different medicines. That was something that Wayne always found interesting, although he didn’t work much with the sheep. Wayne liked to take advantage of the perks of working there by buying the beef and weenies at a discount price for his family. Eating the meat was never an issue for him or his family. It was good stuff.

Taking Good Care

As far as being dirty, Wayne wasn’t. His department didn’t get too dirty during the work and there wasn’t any kind of smell. “There were places where it was stinky. Outside where the cows shit,” Wayne said with a big, hearty laugh. But inside, everything was clean. Wayne was always quite impressed with the cleanliness there, as a matter of fact. “They came in and cleaned up every night. They washed everything down and it was like new every day,” he commented.

Every once in a while, he would go up to the kill floor when he was done with his work in the beef boning area. He only went a few times though. That was the place where the most people got hurt, according to his memory. The one place that no one wanted to go once the work was done in their own department was the hide cellar. The hide cellar was where the hides were shaken and stacked for transport. It was cold and unpleasant. Wayne still wonders why he never had to go in there, but he never asked them why. “I was glad they never put me over there. Everyone hated it. I never had to go over there,” Wayne said with a sly smile.

The Best Part – the Pay

Wayne liked having a study job and pay check. For him that was the best part of the job – the study pay and study work. And the money of course. The money was good enough that when Wayne started working there at 16 he didn’t look back. He never felt school was a good match for him and he figured if he could get good pay why not do it at 16? So that’s what he did. While working at Swift he got married and had a couple of kids and just lived the dream.

He made some good friends, one named Dale Vey who he considered as one of his best friends. “He was the man in pork,” Wayne said. He was in charge of the belt cutter and did the job with great finesse. Dale was kind and honest with everyone he came in contact with. Wayne would often eat lunch and spend some time with him after his shift over at Stockman’s just across “the way” from Swift. “I would have to say he was my best friend. He was a good worker,” Wayne said.

Wayne was part of the union because everyone that worked there just was. He felt the union rules made the job better and he appreciated all his co-workers and his bosses. He talked and had fun with his co-workers, but didn’t really care to associate as much with him bosses for some reason. Looking back, he doesn’t know why now.

Things Turn Sour

Things got a bit ugly for Wayne in 1957. As mentioned before, he was married with two young children when he woke up one morning for work and found his wife had left the family. He was in shock and turmoil. For a little while, he didn’t tell anyone at work and just tried to hide it. He would get up and get his children settled before he went into work but it got more and more difficult. He would often show up late for shifts and his boss was giving him a hard time. They called him in to talk to him about his tardiness. “They pissed me off,” Wayne said. When they called him in, he explained his situation with his wife and children and the boss didn’t believe him. “He thought I was lyin’!” Wayne exclaimed. “Who would lie about something like that?” he said. “So, they canned me. I walked out of there. It made me so mad,” Wayne said, the disgust in his voice rising even after all these years.

It didn’t take long for his boss to realize he was wrong to mistrust Wayne. “He came and apologized to me but it was too late, you see,” Wayne said. He couldn’t go back and he needed to move on. He worked hard and got his contractor’s license and could soon provide for his family again.

But he never stopped following the goings-on at Swift for the rest of the years they were open. “I still can’t believe they packed up and moved out like that,” Wayne said. “They was doing so much good business. I was just shocked,” he added. As the years have passed, Wayne holds no ill will for Swift at all. He enjoyed the work and the how he was taught to work while he was there. The good pay helped him to stay on his feet when times got tough when his wife left and he was still able to care for his family. He also appreciated the way Swift was active in the community. “They was good for me.”

Rachel J. trotter

author

Rachel J. Trotter is a senior writer/editor at Evalogue.Life – Tell Your Story. She tells people’s stories and shares hers to encourage others. She loves family storytelling. A graduate of Weber State University, she has had articles featured on LDSLiving.com and Mormon.org. She and her husband Mat have six children and live on the East Bench in Ogden, Utah.

tell your story

Evalogue.Life was hired to capture the history of the Ogden Union Stockyards and the old Swift meat packing plant, including oral history and other research. These vignettes were written by Evalogue.Life team members.