Mike Casey

A New Idea Brings Fresh Faces to Swift Property

Bert Smith’s son-in-law marries business and pleasure with boat shop

Bert Smith’s son-in-law was a lover of boating. The Swift property was a unique, but perfect spot to sell them.

Mike Casey

In 1971 Mike Casey, vice president of Smith and Edwards, was running Kammeyer’s after Bert Smith had purchased the clothing store on 24th Street near Washington Boulevard. The spot was quite successful and they started to sell boat supplies and do gun repair in the spot. Casey enjoyed the location and the job and it was quite successful. Things changed at the location they day the new Ogden City Mall was announced. There would soon be no more Kammeyers.

Mike Casey was the vice president of Smith and Edwards. Opening a boat shop at the Swift Property proved to be a successful move for the business for a short time.

But Bert Smith was never one to let a deal go badly and he started looking for another location that would be useful. He had purchased the old Swift building, located in West Ogden on the other side of the 24th Street viaduct in 1969 soon after the old Swift meat-packing plant had closed in a somewhat abrupt manner. The big old building wasn’t in great repair, but it was sufficient for housing surplus and maybe some other business possibilities, pretty ideal for a boat shop in many ways.

A Boat Shop

The one business possibility Casey was a part of was moving much of the Kammeyer’s merchandise to the building including opening up an expanded boat shop and gun repair shop. Casey loved the idea for many reasons. They could expand the boat shop and all the space made it perfect for boat display. They were able to showcase boats and use the second floor to do so. Even so, they were only using about 10 percent of the Swift (now Smith and Edwards) warehouse. The boat shop was located on the main floor of the old building just east of the ramps of the kill floor where the animals had been taken up for slaughter.

Another reason Casey loved the boat shop was that people didn’t believe they could make a go of it in such a bad neighborhood. “I knew we could do it, because it was really a perfect location,” Casey said. “No one thought we could sell nice boats in the area, but we’ve proved them wrong, Casey noted.

And yet a third reason Casey loved opening a boat shop was that he knew at the time the outdoor recreation the Ogden area had to offer. He knew of many people who would love the chance to buy boats and all kinds of boat supplies to use close by on the Ogden/Weber rivers and up on Pineview Dam. All places that were just minutes away from the Smith and Edwards Boat shop. Casey loved to talk to people when they would come into the boat shop because they could share their passions – talking about boating and all of its ins and outs.

Dallas Casey, Mike Casey’s son, said he remembers coming to the boat shop with his dad and how much his dad loved it. “He was really into boat racing and so the boat shop really suited him,” Dallas said.

Mike liked the fact that Smith and Edwards gained a whole bunch of storage space for the thousands of surplus items that could not be stored at the current Smtih and Edwards location in Farr West.

A Successful Venture

Mike said the Smith and Edwards Boat Shop opened in about 1972 and they found much success. They sold ski, recreation and fishing boats. They also sold canoes and river boats. “The market was good,” Casey said. They started selling bass boats and those became popular quickly. They were new on the market at the time and people loved them and loved that they could find them locally. “We were the first bass boat dealers and we did a lot to promote them,” Mike said. They also found great success with basic aluminum boats as well. The location proved to be excellent for display purposes because they could use the second floor for display and the prime location with the railroad tracks because they were able to have boats delivered right to the location. “We could have two to three rail carts in at a time and so we became the top bass boat dealer in the country,” Mike said. They had up to 25 full-size boats on display at all times.

Mike always felt proud to tell people he worked at the boat shop and at Smith and Edwards in general. “It was a landmark part of Ogden,” Mike said, adding that everyone knows where both the Smith and Edwards/Swift building is as well as the Farr West Smith and Edwards location. It was a cool place to be and a bit notorious because of the nature of the neighborhood. He loved that they had so much success, especially because of the location.

Many people surmised that there were issues with break-ins and vagrants in the area, but that wasn’t the case. Occasionally a homeless person may wander the grounds, but there was a caretaker for the area that was there pretty much round the clock that worked to chase many people off if they dared come on the premises.

Unique stories

The biggest heist that went on was a strange one. Mike has a couple of Doberman Pinchers that was loved by their family, but were also known to be intimidating. The store was preparing for a huge boat show in Salt Lake City and had quite a few things that were out and accessible so they put the Dobermans on leashes in front of the merchandise. When they went down to get everything for the boat show they found everything intact except for some empty meat packages and no Dobermans. Someone had stolen the dogs! “The leashes were still there and the dogs were gone,” Mike said with a sigh and a laugh at the same time. “It was the strangest thing. We never did figure that out,” he said.

They would have some strange characters wander around from time to time, but nothing too threatening. But it was a bit of a spooky place – mostly because of the thought of all the animals slaughtered on the top floor of the building, often referred to as the “kill floor.” Legends and myths also circulated about from former employees and through the caretaker of the property.

Mike never felt spooked by the place, but was aware of the spooky nature of the place. “So, why not have a great spook alley for young kids,” Mike thought. He was a leader of youth in his neighborhood and he and a friend created an all-out spook alley at Halloween-time. They of course took the kids to the kill floor, telling them about all the animals slaughtered there as they walked through. They walked the kids up the kill ramp and then walked them back down. “it was the ideal scary place,” Mike said with a little laugh. “We had teenaged boys crying, it was really something,” Mike added. After that, his area leader suggested they not do that again, ever. “It was fun for one year,” he said with another chuckle.

Trouble

But things went south quickly in 1977. The business was going strong – great customers, great inventory and inventory that was moving quickly but a sudden spike in the interest rate changed everything. But that wasn’t all. Along with an 18 percent interest rate, gas prices spiked and the viaduct was torn down, making it nearly impossible to get to the boat shop in an any kind of easy manner. Mike said people would have to go about 20 minutes out of the way just to get to the boat shop because of the missing viaduct. “Any one of those things could have spelled disaster, but all three were definitely a deal breaker,” Mike said. “We had to turn down the lights, the party was over,” Mike added.

Mike and Smith decided it would be best to sell the boat shop and sell it quickly, if that would even be possible. They started looking for a buyer, and surprisingly found one. “We sold it for too cheap,” Mike said. But, nonetheless, they were able to sell it. Mike said the gentleman who bought it was a great guy with high hopes for the space. The name of the shop changed from “The Smith and Edwards Boat Shop” to just “The Boat Shop.”

“The Boat Shop” stayed open for just a couple more years, about as long as it took to rebuild the viaduct.

Still a use

But Smith and Edwards still actively used the Swift building for storage. Mike said the space became a vital holding place for merchandise, especially surplus. They used the space and went back and forth to retrieve supplies almost daily through the 1970s and much of the 1980s. Things like sporting goods, clothing, and other surplus materials proved to be stored well at the Swift building. In the latter part of the 1980s they started two major add-ons at Smith and Edwards in Farr West. Once those add-ons were complete, they relied less and less on the Swift building as a major storage space. It was of course always used to store surplus, but not inventory that was regularly circulated into the store. “We started to phase out using the Swift building once those renovations were complete,” Mike said. But he did note that during that one decade the area was vital for daily use at Smith and Edwards.

Mike visited the spot regularly during those early years, but visited less frequently over the past 20 years or so. He visited occasionally with Bert Smith to go over some things, but not on a regular basis.

Smith and Edwards tried to sell some boats and supplies for a few years in their sporting goods section at the Farr West Smith and Edwards location, but there just wasn’t the space like at Swift. But as time passed and viaduct was re-built, the Swift building became more dilapidated, so it didn’t make sense to re-open the boat shop in that location.

For Mike, the Smith and Edwards Boat Shop was a great venture while it lasted, but not something to re-visit again.

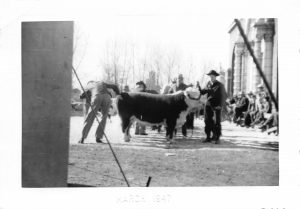

Being that junction gave Ogden the chance to be a haven for the livestock because livestock could be brought in – not only from all parts of Utah – but Idaho as well. With that opportunity, it seemed only natural to have meat packing right there plus it was easy enough to haul refrigerated freight cars in, so the refrigeration industry had a great place to work and work well. “It was just a huge mecca for business,” Witten said.

Witten loves to talk trains and their worth then and now – he sees it and he loves the transition Ogden is making even today. “We have still kept our Junction City and have that same flavor and diversity,” he said as he looked out onto the bustling 25th Street from his office window, still smiling.

Rachel J. trotter

author

Rachel J. Trotter is a senior writer/editor at Evalogue.Life – Tell Your Story. She tells people’s stories and shares hers to encourage others. She loves family storytelling. A graduate of Weber State University, she has had articles featured on LDSLiving.com and Mormon.org. She and her husband Mat have six children and live on the East Bench in Ogden, Utah.

tell your story

Evalogue.Life was hired to capture the history of the Ogden Union Stockyards and the old Swift meat packing plant, including oral history and other research. These vignettes were written by Evalogue.Life team members.