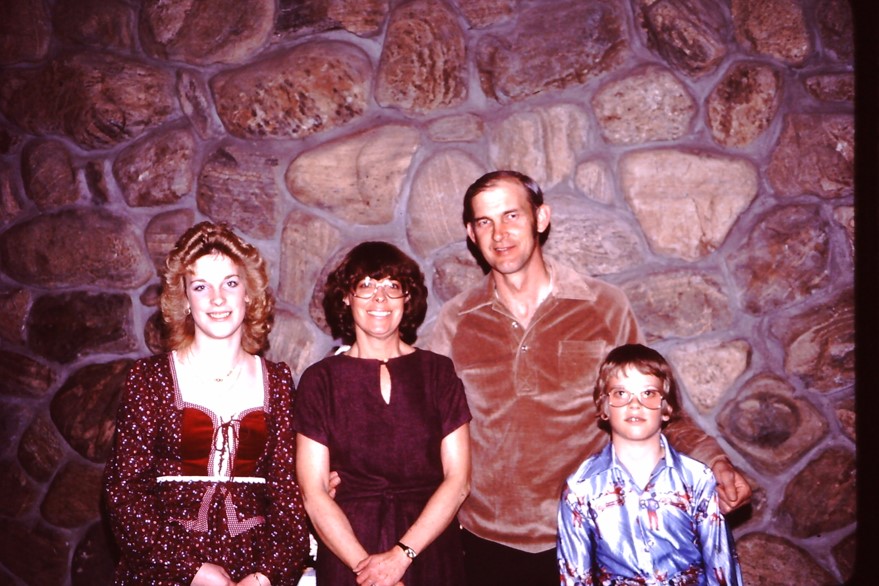

Clair Barrow

Clair Barrow worked the gamut of jobs of Swift. And what do you know? The first job was the hardest!

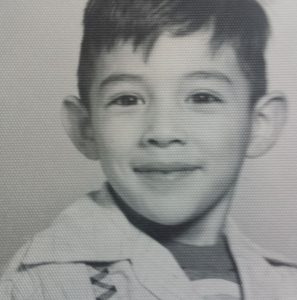

A young boy sets up a nice life for himself with good wages at Swift Meats

He never thought much about the hard work he did at Swift. But now he sees it set him up for a pretty nice life.

Clair Barrow

Clair Barrow learned at the young age of 16 or 17 what it was like to work hard. That’s when he started working at Swift Meats in Ogden, Utah. He worked summers starting in 1956. He worked in nearly all the departments of Swift and while there, but found quickly that his first job was the hardest.

Clair Barrow describes some of the work he did at Swift as “back-breaking.” But he didn’t mind it once he got his paycheck.

THE WORK

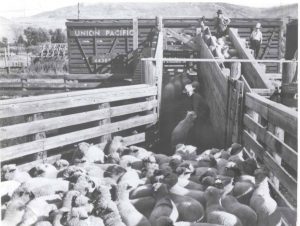

He loaded rail cars on the shipping docks. It was hard, back-breaking work. “It was probably the hardest job down there. You had to be hunched over in those rail cars hauling a half of beef. Them things were heavy. You really built your muscles doing that,” he said, laughing at the memory. The rail cars were packed with ice that was produced in an ice house just across the street from Swift and then traveled back east, mostly to Chicago. Clair would load beef, lambs and pigs on the cars and he always knew he earned his paycheck after a grueling shift in that department.

By 1958 he was married and got offered a full-time gig. At that time, he was able to switch from loading the rail cars to loading trucks with smaller portions of products to go to local grocery stores – about as far as those loads would go is Idaho. While the work was still difficult, it was nothing like what he had done loading the rail cars. In the shipping departments, shifts were round-the-clock, the only shifts at Swift that were.

Clair learned early on that seniority was key at Swift and as different jobs came open that paid more or were desirable people would bid for them and got the jobs based on seniority. Once a person got a job in a different department they had to work their way back up again. But that didn’t stop Clair from trying different jobs to get better pay or better work conditions, although he didn’t really mind any of the work. “Well it was all hard work, but the pay was so good you didn’t mind,” Clair said of Swift. “And they knew they better treat us right because of the union.” Clair attributes the union to the excellent way employees were treated and paid. There had to be a clean work environment, money had to be paid on time and things had to be positive. And Clair always felt they were.

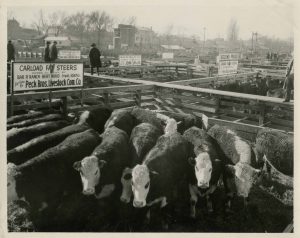

He worked on the “kill floor” for a couple of years – the top part of the building were the animals were brought up to be killed. Many described the kill floor as the one of the worst or hardest jobs in the place, but Clair didn’t think of it that way. It was swelteringly hot and the jobs were sacred for those that had been there a while. “Those were some mean and tough guys there,” Clair said of the men who had the seniority on the kill floor. Pay was based on how quickly you killed and got the animals ready to go so work had to be fast. Clair admitted not a lot of socializing went on during shifts on the kill floor. Clair didn’t actually kill the animals himself – which consisted of knocking the animals in the head with an air gun; but one of his jobs was to tie their legs off and pull their hides. Clair was always amazed by how many animals were killed in a shingle shift. Thousands, he figures some days. Lambs were a premium. He decided this was the case because that’s the kind of meat people liked to eat on the east coast. On the kill floor, there was a beef side and a sheep side and Clair worked both sides.

Often, rumors would start that layoffs were coming to one department or another so employees would start to bid to work in a different spot. That’s why Clair moved around so much. One of his favorite areas to work was in the smoking department. It was cooler and it was where the meats were prepared for packaging. He would work getting the pork ready to be made and packaged into bacon which was where most of the “girls” worked, as Clair put it. He would also prepare the hams and different meats for smoking. It was really the last step before shipment. It was still busy and not easy, but it was less chaotic than the kill floor or the actual loading department for shipment.

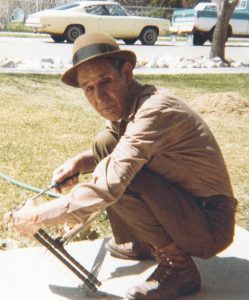

THE ENVIRONMENT

Clair always felt very positive about working at Swift. Of course, for him the money was the best part. “I became a very rich man because of my start at Swift,” Clair said. He was making a lot more money than many others during that time and he was able to buy and provide things for his family that he never dreamed when he started working there. Because he had that extra cash he was able to also make smart investments and buy land. He thinks he wouldn’t have found that success without Swift. And although it closed down, the training he received there helped secure his career as the meat manager at Stop and Shop where he finished out his career.

Clair feels strongly that the union kept Swift honest, although he really liked all his bosses and the people who worked in the office – none of which were part of the union.

Their work clothes were provided at the start of each shift. White shirts, pants and suspenders. After the end of a shift they were permitted to go shower and leave their dirty clothes behind. Their clothes had their work numbers (his was 280) and they would be ready to go at the beginning of the shift at their lockers the next day. Clair didn’t have a strong dislike for the smell of Swift for that reason. He always appreciated that at night workers came in and cleaned everything so they could start fresh each day. While he doesn’t think that was a federal law, it was part of the union. He was never required to wear gloves for any of the work he did though. He never felt like he was being watched over or anything like that, he always felt that he was treated with utmost respect.

There was a cafeteria with “some of the best food you ever ate.” There was a little bridge he would walk across on the north side of the building and that’s where the showers and cafeteria were. The food cost of course, but it always tasted good and fresh, Clair said. He didn’t often eat there because his wife sent a lunch for him, but it was nice to know it was there if he was ever in a pinch. Clair would often start his day at Stockman’s which was a café just west of Swift. “I loved that old place. I’d get me a short stack and coffee every day before work,” Clair said, smiling at the thought. There were pinball machines and it was a place to be social for many of the guys. Quite a few Swift employees would hang out there after work and drink a bit of beer. Clair wasn’t a part of that. “I didn’t want to get into too much trouble with Judy,” Clair said with a wink. Judy was his wife!

Clair enjoyed many of the fringe benefits of Swift – benefits like being able to buy the meats at a deep discount. He liked to take advantage of that and still loves himself a big streak to this day. “Oh, eating meat never bothered me a minute. I could eat steak every night!” he exclaimed.

Clair always thought Swift cared and wanted to contribute to the community. At least once per year Swift paid employees with $2 bills so they could see where people were spending their money in the community. “They wanted to see what impact they were making. They were proud of that,” Clair said. Clair liked the uniqueness of that perk, so did his kids. His daughter Shelly said she always thought her mom got those $2 bills from the bank. “No I just gave them all to her, like all the rest of my money,” Clair said with a tease in his voice. He remembers that he started at $2.65. “Of course, it only cost $1500 to buy a nice car back then too,” he said with a big laugh.

He liked the fact that he could “beat the clock” so to speak and get paid extra. If they wanted him to do a job in an hour and 15 minutes and it only took an hour, he would get paid for the hour and fifteen minutes. He loved when those work times would go fast like that. He also spent some time pulling some double shifts. Every so often they would ask for people to go and help render the lard from the animals. They would take the lard and send it off to a plant where they make all different kinds of oils. So Clair would work his main shift then pull another shift rendering lard. He made big stacks of cash during that time.

The Social Life

Clair made life-long friends in his time at Swift. He didn’t necessarily socialize while on shift, but socializing was done at places like Stockman’s and in the cafeteria. Plus, he was not alone in making the great money and many of them bought land and horses near each other and stayed friends and neighbors long after Swift shut down. They didn’t necessarily work together again, but had that Swift tie that started long-term friendships. Clair worked with his older brother which was a bonus for him. His brother got him the job but always had seniority over him, which never bothered Clair – he was his big brother after all.

The Shut Down

Clair admits it was somewhat of a shock when they learned things would shut down. The “bosses” let the employees (he thinks there were about 300) know about two months ahead of time that they would be shutting things down so they could find other work. Clair immediately got a job at Great Salt Lake Mineral, but found that he hated the work there fast. He finished out his time at Swift and saw things slowly shut down. They had opened a new plant in Arizona and offered the employees a chance to transfer there. It wasn’t something Clair was interested in. He had a family in Utah and didn’t feel the desire to leave. The union helped keep things on the up and up and he felt okay with the way they were treated in the end. Other guys followed at GSL, but also found they didn’t like the work. Many went to Ogden Dress Meats and that’s where Clair ended up eventually as well and then onto Stop and Shop grocery store where he was a talented butcher.

Clair always considered Swift to be a great place to work. “It was a huge operation down there. Between the Stockyards and Swift and the ice house. There was a lot going on and it really put Ogden on the map. Swift really kept those Stockyards going too,” Clair said. He was always glad to be a part of that huge operation.

Rachel J. trotter

author

Rachel J. Trotter is a senior writer/editor at Evalogue.Life – Tell Your Story. She tells people’s stories and shares hers to encourage others. She loves family storytelling. A graduate of Weber State University, she has had articles featured on LDSLiving.com and Mormon.org. She and her husband Mat have six children and live on the East Bench in Ogden, Utah.

tell your story

Evalogue.Life was hired to capture the history of the Ogden Union Stockyards and the old Swift meat packing plant, including oral history and other research. These vignettes were written by Evalogue.Life team members.